Home » The Medical Marijuana Myth

The Medical Marijuana Myth: Why We Advocate for Phasing Out “Medical” Marijuana

Jump to:

- Introduction

- History of Marijuana

- Rationale for the Current Medicinal Marijuana System

- Is Marijuana Medicine?

- Perception of the Risk and Harm of Marijuana

- Myth 1: Marijuana Is Not Habit Forming and Marijuana Withdrawal Does Not Exist

- Myth 2: “Reefer Madness” Was and Remains Just a Scare Tactic

- Myth 3: Marijuana Side Effects? What Side Effects?

- Conclusion

- Citations

In states where marijuana is approved for recreational use, we propose the gradual phasing out of the medical marijuana system in favor of one class of marijuana.

Legalized marijuana is part of America’s future. The federal government may still classify it as a Schedule I drug, but, in most states, the public has reasonable access to marijuana for at least some purpose. We believe that development is, in general, a good thing.

Marijuana sales are typically bifurcated and regulated for recreational or medical purposes. To purchase medical marijuana from a dispensary, you first need a recommendation from a licensed doctor, and you must have a condition that qualifies for medical marijuana use. This process reinforces widely held beliefs that marijuana is a medication comparable to FDA-approved therapies which have been researched for years and undergone clinical trials. In truth, medical marijuana has only a veneer of legitimacy. That legitimacy is not warranted considering the serious gaps in current research.

Marijuana’s treatment as a class of medicine is unlike any other class of medicine that currently exists – and functions largely outside of conventional treatment settings. Medical marijuana is treated as a panacea for many medical issues with little clinical research proving whether it treats those issues or if there are any risks with using medical marijuana, often chronically and in high doses, as a treatment.

With that in mind, this white paper provides information on why the issues with this overlap must be addressed. While we favor phasing out the medical marijuana infrastructure in territories where marijuana is approved for other purposes, we also advocate for:

- Legalization of adult-use marijuana in the United States

- Efforts to advance the study of marijuana by lowering barriers to research

- Additional physician guidance for patients seeking to use marijuana for any purpose, including for symptomatic relief

- Public health efforts to educate marijuana users regarding its risks

- Introduction of support systems for dependent users in need of assistance

Medical marijuana may have been introduced with good intentions, but it has the effect of lowering perceptions of risk and confusing at-risk patients, all under the guise of legitimate medical application. The research on marijuana for most medical purposes is inconclusive, and effective government endorsement only further complicates matters for people suffering and physicians responsible for prescribing it.

History of Marijuana

Before delving into current issues with the bifurcated marijuana system across the United States, it is important to understand the history of marijuana and how the current dynamic came to be.

Marijuana has been used for thousands of years for industrial, recreational, religious, and medicinal purposes. Once valued as a versatile herbal medicine, marijuana has held a volatile place in the medical field since the beginning of the 20th Century. Until recently, it seemed the flowering plant was destined to fall by the wayside: it was classified as a substance of abuse, condemned by governments, and contributed to the problems of drug trafficking. However, research into marijuana’s potential medicinal benefits changed the public perception. Marijuana now receives increased attention from patients, physicians, and governmental regulators across the globe (Pain 2015; Pisanti and Bifulco 2017).

Early History

Historians and archeologists believe Cannabis sativa has been grown for at least 12,000 years. It was initially cultivated for its fiber and grain. The fibers and stalks of hemp, a non-psychoactive variety of Cannabis sativa, was found to be particularly useful in the development of numerous products including paper, textiles, and rope (Pain 2015; Baron 2015). The exact geographic origin of marijuana is unknown, but it is believed that the plant arose in Central Asia and subsequently spread throughout Asia and Europe, following the migration patterns of humans (Russo, History of cannabis and its preparations in saga, science, and sobriquet 2007). Carbon dating of archeological remains from the Yang-shao culture in China has confirmed the use of marijuana fibers in the form of hemp dating as far back as 4,000 BC (Li 1974). Marijuana spread to the United States after the arrival of Columbus, and the industrial benefits were capitalized here.

The earliest evidence of the medical use of marijuana dates back to 2,700 BC, where the Chinese Emperor Shen Nung described it as a remedy for gout, malaria, rheumatism, and constipation (Liu and Powles 2006). In Egypt, starting around 1,700 BC, scholars began to outline medical remedies for a number of ophthalmic, gynecologic, and infectious disorders using marijuana, indicating suspected antibacterial, antipyretic, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory effects (Russo 2007). A number of ancient societies in Asia and Europe, including the Greeks, Romans, and Mesopotamians provided medical indications for the use of marijuana. Some historians even argue references can be found in the original Biblical texts (Ibid). In India, literary descriptions of marijuana were outlined as early as the sixth and seventh centuries. By the tenth century, scholars were clearly describing the narcotic and pain-relieving properties of the plant (Chopra and Chopra 1957). The first archeological evidence supporting the medical use of marijuana came from a burial cave near Jerusalem. The skeleton of a 14-year-old girl who had presumably died during childbirth in the fourth century was found to have burnt plant remains on her abdomen. Chemical analysis showed the remains contained THC. Archeologists concluded marijuana had been burnt in a vessel and that the girl inhaled marijuana smoke during her efforts to deliver the baby (Pain 2015). Cannabis has long held an important role in human culture, across a variety of cultures and regions. It was well-known before the modern era to be a potent, versatile therapeutic.

The Rise of Modern Western Medicinal Interest

The Western world was first introduced to the medicinal uses of marijuana in 1839 by Irish physician William Brooke O’Shaughnessy. Dr. O’Shaughnessy had spent time in Calcutta where he observed people using marijuana for a number of purposes including digestive system support, improvement of their overall sense of well-being, and as a narcotic.

Impressed, he began to test the plant’s effects in animals. Based on his experiments, he ascertained that the plant was safe for use and made extracts of marijuana resin which he placed in pills or dissolved in alcohol. He administered these preparations to select patients who suffered from epilepsy, rheumatisms, cholera, or tetanus. He deduced the plant had analgesic and myorelaxant properties. His work was of critical importance in introducing Indian hemp to British and North American physicians (O’Shaughnessy 1843; Pisanti and Bifulco 2017, Pain 2015).

Following O’Shaughnessy’s work, systematic research on marijuana began to proliferate in the Western World. During the second part of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, over a hundred studies were published in Europe and the United States. Researchers explored the impact of marijuana on pathologies ranging from migraine, neuropathic pain, insomnia, hysteria, and stroke to asthma, emphysema, tetanus, and uterine hemorrhage. Pharmaceutical companies such as Merck and Eli Lily developed analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-spastic drugs using marijuana extracts. (Pisanti and Bifulco 2017; Russo, History of Cannabis as Medicine: Nineteenth Century Irish Physicians and Correlations of Their Observations to Modern Research 2017). The presumed impact of marijuana on migraine relief was so promising that in 1915 Dr. William Osler, considered the “Father of Modern Medicine”, stated that when treating migraines, “Cannabis indica is probably the most satisfactory remedy”. (Baron 2015). It was an exciting time in marijuana research. Unfortunately, just as the research was starting to show promising results, it suffered major legal and social setbacks.

Growing Restrictions and Fear of Reefer Madness

Even though the body of research on the benefits of marijuana was reaching its peak at the end of the 19th century, the use of medical marijuana was starting to decline. The pharmacologically active components of marijuana were still unknown, and therefore the drug preparations suffered from standardization difficulties. Manufacturers were unable to accurately titrate clinical dosing or ensure quality control. Due to the variable effect marijuana medications had on patients, it struggled to gain broad acceptance (Pisanti and Bifulco 2017; Russo 2007).

While medicinal use declined, recreational use grew in Western cultures. New research helped to popularize the exploration of the psychoactive effects of marijuana. For instance, French psychiatrist Jacques-Joseph Moreau undertook marijuana trials on himself and his students in 1840 and detailed the psychoactive effects in research journals. Soon after, use of marijuana grew among the intellectual elite in Europe. The Club des Hashischins (Club of Hashish Eaters) emerged in Paris and was frequented by famous poets and authors like Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Charles Baudelaire, and Honoré de Balzac. The group was dedicated to exploring the drug-induced experiences caused by hashish. (Pisanti and Bifulco 2017).

Public and government concerns began to emerge about the uncontrolled circulation of marijuana for recreational purposes. This concern was driven in part by economic worries that marijuana use was impacting the productivity of slaves and indentured colonial workers and in part by propaganda that marijuana was a drug of abuse used by minority and low-income communities that lead to psychosis, mental deterioration, addiction, and violent crimes (Pisanti and Bifulco 2017, Baron 2015).

Throughout the Western world, governments began working to restrict marijuana use. In the U.S., local laws started to emerge after 1860 requiring medicines to indicate if marijuana was found in the preparation and prescriptions from doctors for use and The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 enacted the first national regulation that medical preparations containing marijuana be labeled. In 1925, international drug control treaties between the U.S., Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, China, Japan, Persia, and Siam banned the exportation of Cannabis indica to countries that prohibited its use. Recreational use of marijuana was banned in the United Kingdom in 1928. In 1937, the U.S. government passed the “Marijuana Tax Act”, which did not forbid the use of marijuana, but made the purchase and preparation of the plant so expensive that experimentation into the medical uses of marijuana were all but discontinued. In 1941, despite protest from the medical community, marijuana was removed from the United States Pharmacopoeia and National Formulary, which contains standards for medicines and dosage forms, among other important details (Pisanti and Bifulco 2017, Baron 2015). Its removal was basically a death knell for its acceptance as a product with legitimate medical uses.

Marijuana started to be considered a drug of abuse and the resurgence of recreational marijuana in the 1960s and 1970s by anti-establishment groups further drove this perception. Cannabis came to be associated with the psychedelic hippie counterculture movement. In August 1970, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Health, Dr. Roger O. Egeberg recommended that marijuana be classified a Schedule I substance, in the same category as heroin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Dr. Egeberg reasoned, “Since there is still a considerable void in our knowledge of the plant and effects of the active drug contained in it, our recommendation is that marijuana be retained within Schedule I at least until the completion of certain studies now underway to resolve the issue.” The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 was passed shortly after this recommendation was published and marijuana was classified as a Schedule I substance, not because of scientific evidence, but due to lack of scientific knowledge. (Pisanti and Bifulco 2017, Baron 2015). Shortly thereafter, the United Kingdom classified marijuana as a class B drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act of 1971, making it illegal to grow, process, produce or supply the drug (Liu and Powles 2006). That same year, the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances determined that only authorized people in supervised laboratories could carry out research on marijuana (Pain 2015). These restrictions ended up having the effect of limiting the opportunities to research marijuana and its potential medicinal effects.

With the growing legal barriers to research and the widespread negative opinion of marijuana as a narcotic, it looked like medicinal research of marijuana was destined to end. However, small groups of researchers continued to study the plant and their findings at the end of the 20th Century propelled research forward in new and exciting directions. In the 1990s, the discovery of the receptors for cannabinoids and the characterization of the endocannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system, the effective biologic target of phytocannabinoids, renewed scientific interest in marijuana, leading to the publication of thousands of papers over the following decades highlighting the pharmacologic potential of the plant and its components.

Rationale for the Current Medical Marijuana System

While it is clear marijuana has been used to treat medical issues since time immemorial, modern research methods help us better understand the true impacts of marijuana in a medicinal sense, providing more concrete evidence of its effectiveness or lack of effectiveness and potential hazards.

But even before diving into the discussion over what research says or does not say about marijuana, there are ethical arguments used to determine the rationale behind why physicians prescribe medical marijuana. This context is important in understanding the overall system and its actors’ motivations.

Patients Have a Right to All Beneficial Treatments

The argument in favor of medical marijuana is grounded in ethical principles like beneficence and nonmaleficence. Patients have a right to all beneficial treatments and studies have shown medical marijuana is effective at reducing some patients’ symptoms, such as chemotherapy-induced nausea, most famously. In fact, the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) has approved specific drugs derived from marijuana for those purposes. Because patients have a right to all beneficial treatments, denying them this violates their basic human rights. This is why the argument for allowing physicians to help patients access marijuana in states where marijuana is not approved for other purposes is strong.

Of course, this ethical argument is cloaked in an important caveat. While we agree that denying physicians the right to even discuss alternative treatment options with their patients, including marijuana, is immoral and violates a patient’s right of informed consent, that does not necessarily mean medical marijuana deserves the same treatment as drugs the FDA has deemed legitimate medical options.

The arguments focusing solely on beneficence and nonmaleficence in the prescribing of medicinal marijuana to treat medical issues are important but ignore this crucial fact about medical marijuana’s relationship vis-a-vis other medical options. It is this divergence where questions about the veneer of legitimacy medical marijuana programs provide arise and generally revolve around the question of whether or not marijuana is medicine.

Is Marijuana Medicine?

Whether or not marijuana in its current form is medicine is the key question of this debate. We believe that the “medical marijuana” nomenclature provides marijuana with a medical legitimacy it may not deserve that favorably compares it to other medicines that have been researched for years and undergone clinical trials. This has the effect of confusing members of the general public into thinking medical marijuana has the same controls and regulations applied to it as any other drug.

In a world where messaging matters, how medical marijuana is portrayed to the public affects its treatment on the policy level. This is why the phrase “medical marijuana” is so important and why whether or not marijuana has true medicinal impacts is a question that must be answered.

Opiates and Marijuana: Clinical Requirements

Marijuana is, of course, not the first plant to be utilized for both illicit and legitimate medical purposes. Opium is another and while there is currently an ongoing national debate about the use of opiates and their propensity to be abused, those drugs still underwent clinical trials and rigorous testing. That is not the case with marijuana treatments.

Ruben Baler, Ph.D., an expert on the neuroscience of substance abuse and addiction, believes marijuana is medicine the same way opium is a medicine. Like marijuana, opium is a plant with active principles, which can be synthesized into drugs with real medical purposes after undergoing clinical trials. Dr. Baler believes marijuana should be treated the same way.

Like opium, marijuana has ingredients with medical potential but those ingredients are complex. Before prescribing them for specific medical applications, evidence-based conclusions must be determined through the traditional trial process. As Dr. Baler says, “we don’t deploy medications with that kind of complexity” without studying their potential impact. “That wouldn’t be a medicine, it would be ‘magic realism.’” According to Dr. Baler, the pendulum on medical marijuana has swung too far towards just acceptance based purely on anecdotes. That pendulum must swing back towards science and evidence. (Baler 2021).

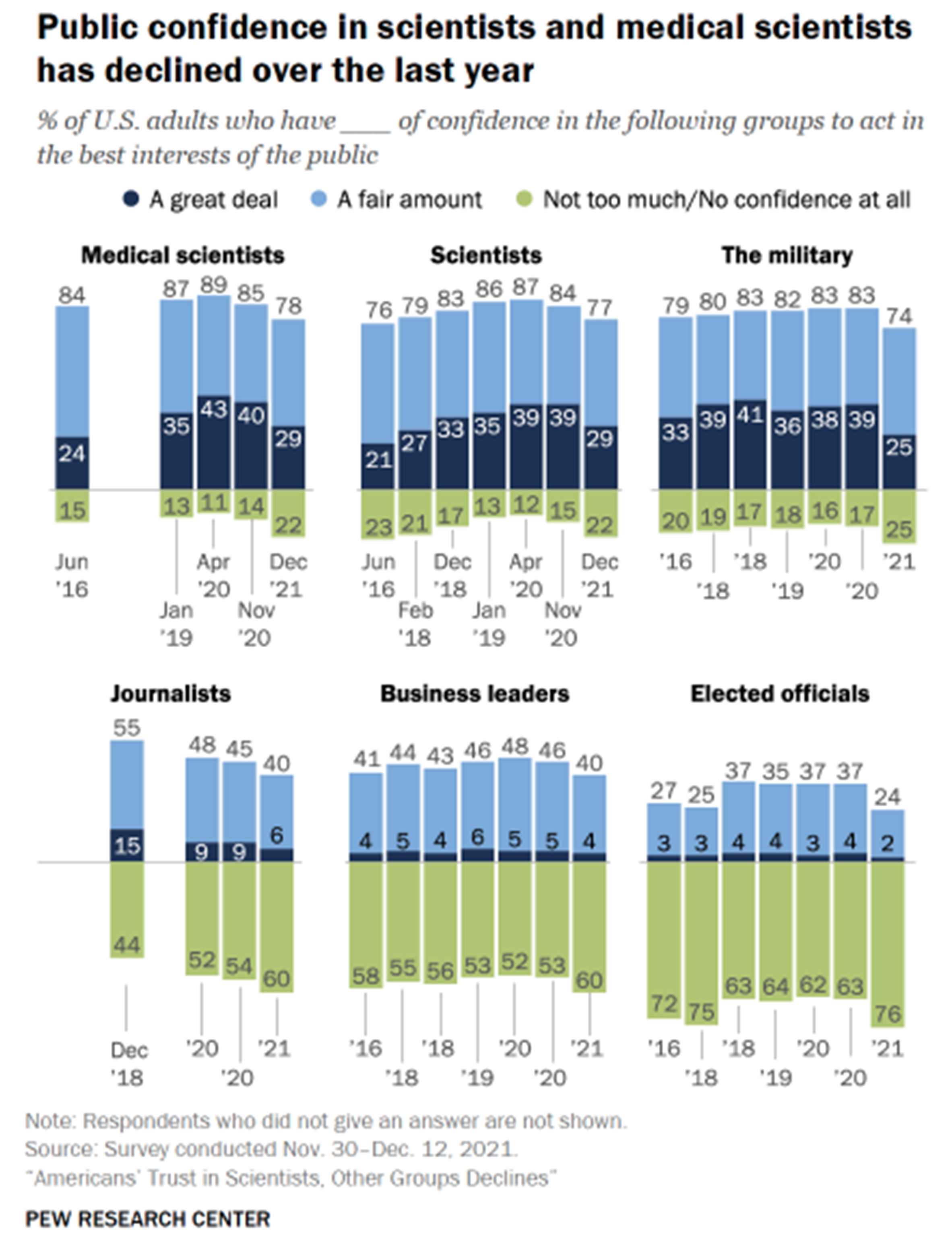

Medical scientists have seen the public’s trust in them wane over the last several years. Many supporters of medical marijuana share a broader skepticism about doctors, scientists, and the scientific field. While some may think this a harmless side effect of the increased acceptance of marijuana as a potential treatment option, it could also have the effect of dissuading patients from seeing licensed doctors for medical consultation and instead going to medical marijuana companies for the same information. These two actors are not on the same level. One group recommends products and treatment options, which have been through rigorous scientific studies. The other pushes their own products as solutions to any number of medical problems but without clarity as to those products’ potential costs or benefits.

Aside from the obvious issues with medical marijuana companies filling the dearth of research into the costs and benefits of marijuana with their own heavily biased research, the fact that this type of pseudoscience is taking advantage of the public’s declining lack of trust in experts, which one can see in the figure below (Kennedy, Tyson and Funk 2022). The anti-vaccine movement, which began years ago but has culminated in the negative reaction to the development and delivery of the vaccines against COVID-19 is but one example of the public’s growing distrust of experts whose views and knowledge underpin much of the stability of the country’s key institutions.

The difference between the two groups could not be clearer, but for many patients, the line is blurred and both are viewed as two sides of the same coin.

For instance, some medical marijuana companies feature FAQ sections on their websites in which they direct patients to consult with the company to find a doctor who will recommend marijuana as a treatment if their normal doctor will not. In addition, dispensary staff are portrayed as experts who will guide patients in selecting correct products and dosages. This is a dangerous precedent, which legitimizes medical marijuana as a viable medicine when it does not deserve to be labeled as such.

Without a set of large-scale studies proving either that medical marijuana products are viable treatment options for various medical issues or options that have limited benefits and potentially serious side effects, the government and the medical community are at a disadvantage.

The medical marijuana industry is in a position to take advantage of this lack of research by pushing claims that may or not be true, but tap into public distrust of the medical community (often, ironically, because they are too focused on just making money) and the conventional wisdom that marijuana is safe for people across the board. It is this veneer of legitimacy that must be stamped out.

Perception of the Risk and Harm of Marijuana

Throughout much of the 20th Century, marijuana had a stigma attached to it. A lot of this stigma arose from the 1936 film, Reefer Madness, which gave a rather melodramatic account of what happens when one uses marijuana. But marijuana’s use amongst the counterculture movement of the late-1960s also contributed to this stigma. Combine the influence of Reefer Madness and the association of marijuana with “hippies” with the government’s classification of marijuana as a Schedule I substance, and public perception of marijuana was quite negative as it was often viewed as high-risk and a “gateway drug”. But that is no longer the case.

The Winds of Change – From Malevolent to Benevolent

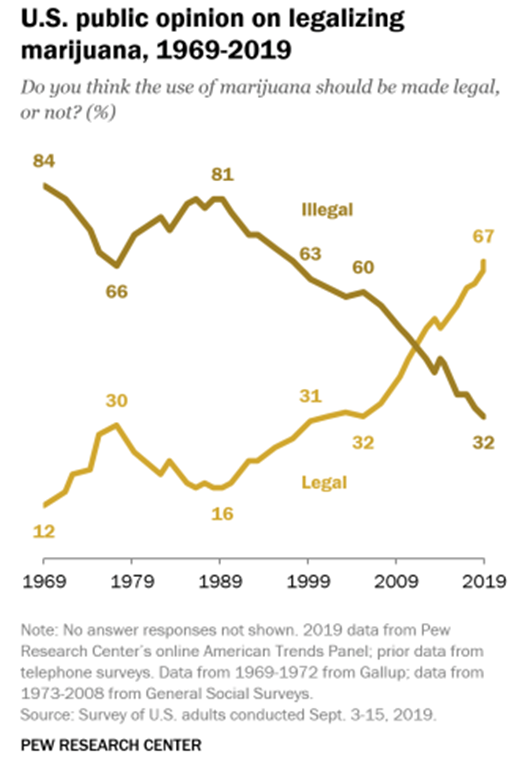

Those perceptions are now antiquated. As the following chart from the Pew Research Center shows, U.S. public opinion on the legalization of marijuana has flipped over the last 50 years showing that the association of marijuana with Reefer Madness and the dangerous counterculture has washed away (Daniller 2019).

Part of the switch in public opinion is related to how risky and harmful people now see marijuana. As marijuana has become more ubiquitous, thanks to the legalization of it in many states for both medicinal and recreational purposes, the percentage of people who perceive marijuana to be highrisk has decreased since 2002 (41.6% to 26.1%) while the percentage of people who perceive it to be low risk has increased (16.8% to 35.8%) (Levy, et al. 2021). Of course, this trend is not necessarily related to the potency of marijuana or the actual risk factors, or harm associated with its use. In reality, it is more likely related to the continued increase in the legalization of marijuana in the majority of states around the country. As states have given marijuana a seal of approval, public perception has subsequently adjusted. According to a separate Pew Research Center study from 2021, 91% of Americans now believe marijuana should be legal for either medicinal and recreational use or just medicinal use (van Green 2021). There are divergences in the data with older Americans less supportive of legalizing marijuana, not surprisingly, but as that generation dies off, public perception of marijuana will continue to remain favorable.

Confluence of Speed and Lack of Critical Information

These changes in public perception are influencing policymakers and contributing to the fast pace of legalization across the country. While most view this as a positive development, there are critical issues with the movement and the speed at which it is finding success.

Simultaneous with the increase in recreational drug use and the spread of legalization, there has been a “steady erosion in the public perception of the harms associated with the use of popular drugs.” (Weiss, Howlett and Baler 2017). As the legalization of marijuana has continued apace, especially on the medicinal front, the issues previously discussed are proving to be more problematic. The research is not there to adequately link marijuana to positive health benefits. There are too many unknowns. And, “when policy changes are hurriedly implemented without the required input from the medical, scientific, or policy research communities…initiatives are bound to magnify the potential for unintended adverse consequences in the form of far ranging health and social costs.” (Ibid). Laws are currently being written and rewritten without a commitment to developing these laws based on science and research to highlight potential issues. Much of these declining perceptions have the effect of overemphasizing the benefits while reducing concern about the downsides. Similar to other medical treatments marijuana may have benefits but also has side effects.

For example, one area in which there is a huge knowledge gap is related to THC potency and its impact on health. The average concentration of THC has increased from around 3% in the 1980s to 12% more recently. (Ibid). Of course, that concentration is only from research into marijuana seized by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency and does not include research into products currently being sold in dispensaries around the country, which purportedly include products with a THC concentration of over 70%. (Ibid). “The effects of such high levels of THC exposure on the brain are unexplored, and may be particularly hazardous for young users…” (Ibid). To continue to link recreational and medicinal marijuana without understanding the effects of such high levels of THC is dangerous and no other medicinal treatment option on the market would be treated so cavalierly.

The intensifying concentration of THC is just one concerning aspect of the proliferation of marijuana throughout the country and how proliferation is affecting our perceptions of risk. It is possible while the perceptions of the riskiness of marijuana crater, the actual risk associated with the product is increasing. The only way to determine whether this is actually true and what health risks currently exist is by encouraging more in-depth research into the marijuana products Americans are using for both recreational and medicinal purposes.

Myths about Marijuana’s Physically and Psychologically Addictive Properties

Unfortunately, another problem with the confluence of medicinal and recreational marijuana use are the myths associated with marijuana and how it impacts its users. Marijuana is often viewed as only providing positive benefits, especially when compared with other Schedule I drugs like heroin, bath salts, ecstasy, and quaaludes. But this conventional wisdom ignores scientific and important anecdotal evidence about the risk of marijuana use, both physical and psychological.

Myth 1: Marijuana Is Not Habit Forming and Marijuana Withdrawal Does Not Exist

One of the primary myths associated with marijuana is, unlike other higher-risk drugs, marijuana is non-habit forming, or not addictive. This is one of the more dangerous and pervasive myths regarding marijuana. In reality, marijuana users are at risk of developing cannabis use disorder (CUD), formerly referred to as abuse, dependence, or addiction. CUD is characterized by difficulty controlling intake, use in risky situations, social impairment, development of tolerance, and withdrawal within a period of 12 months.

Persons with CUD may suffer from problems at school or work, give up activities they previously enjoyed, or withdraw from their social network (Patel and Marwaha 2022). It is estimated that globally over 13 million individuals met the criteria for CUD in 2010, a point prevalence of 0.19% (Degenhardt, et al. 2013). In the U.S., an estimated four million individuals had current CUD in 2016, a prevalence rate of 1.5% (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2016). Research suggests 9% of individuals that report ever using marijuana ultimately develop CUD (Lopez-Quintero, et al. 2011). Research has shown that the transition to cannabis dependence occurs considerably more quickly than the transition to nicotine or alcohol dependence (Lopez-Quintero, et al. 2011).

While general marijuana usage has increased substantially over the last decade, it is not entirely clear whether the prevalence of CUD has increased as a result. One national U.S. survey found stable rates of dependence between 2002 and 2014, while another study found that the rates of cannabis use and CUD doubled over the same time period (Hedden, et al. 2015; Grucza, et al. 2016; Hasin, Saha, et al. 2015; Weiss, Howlett and Baler 2017). Further analyses are underway to clarify the reason for this difference.

CUD is clearly a concern and refutes the broad conventional wisdom about marijuana not being addictive. And, of course, with addictive properties comes the potential for significant withdrawal symptoms. Before the 1990s, many doubted that quitting marijuana after periods of heavy use could lead to similar symptoms of withdrawal seen in other illicit drugs. However, as marijuana use began to rise over the next two decades, more patients began to seek treatment for marijuana-related disorders, including dependence, cognitive deficits, and psychosis.

Researchers began to see that discontinuation of regular cannabis use was frequently associated with behavioral, emotional, and physical symptoms that disrupted daily living and were associated with relapse (Bonnet and Preuss 2017). Based on support from neurobiological, clinical, and epidemiological studies, cannabis withdrawal syndrome (CWS) was added to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) in its 2013 edition (Livne, et al. 2019).

Cessation from heavy or prolonged cannabis use result in mood and behavioral symptoms which include irritability, nervousness/anxiety, sleep difficulty, decreased appetite or weight loss, depressed mood, and agitation.

Individuals can also suffer from physical discomfort and complain of headaches, night sweats, abdominal pain, tremors, dizziness, and fatigue (Bonnet and Preuss 2017) In a study of 1,527 marijuana users, the most common side effects experienced post-cessation were nervousness/anxiety (76.3%), hostility (71.9%), sleep difficulty (68.2%), and depressed mood (58.9%) (Livne, et al. 2019), CWS is diagnosed when, within a week after cessation of heavy prolonged use, an individual has three or more symptoms of withdrawal.

Generally, symptoms of withdrawal begin within the first 24 hours of abstinence, peak by day three and can last for up to two to three weeks (Patel and Marwaha 2022; Bonnet and Preuss 2017).

As CWS is a relatively new diagnosis, the exact prevalence of CWS is unknown. Studies have estimated that anywhere between 35% and 90% of individuals seeking outpatient cannabis detoxification may develop symptoms of CWS (Bonnet and Preuss 2017; Livne, et al. 2019). In the first study to use DSM-5 criteria on the prevalence of CWS (a patient had to have three or more symptoms), the authors estimated the prevalence of CWS at 12.1% among cannabis users (Ibid).

A variety of heritable and environmental characteristics appear to influence the severity of withdrawal symptoms experienced during a cessation attempt. These include personal history of depression, anxiety, panic attacks, and personality disorders as well as family history of depression and substance abuse (Livne, et al. 2019).

Gender and age also appear to play a role, as women and younger users (18-29) generally appear to suffer from more severe symptoms (Schlienz, et al. 2017; Sexton, Cuttler and Mischley 2019). Interestingly, medical users tend to experience more undesirable withdrawal symptoms compared to recreational users, which is thought to be due to the added therapeutic benefit associated with marijuana use for medical reasons (Sexton, Cuttler and Mischley 2019).

The primary risk factors for cannabis withdrawal are thought to be intensity and recency of marijuana use (Bonnet and Preuss 2017). Severity of marijuana withdrawal increases with that of marijuana dependence, and patients with cannabis use disorder are at the highest risk (Livne, et al. 2019).

Importantly, the medical community has been slow to respond to this growth in CUD and CWS. The changing social and legal landscape surrounding marijuana use, coupled with the increasing potency of marijuana (Carliner, et al. 2017), leaves vulnerable populations at even greater risk to the potential harms of marijuana use and dependence.

What this research shows is marijuana has properties similar to other high-risk substances of abuse. This does not mean marijuana and marijuana users deserve the same severe legal treatment as other Schedule I users and substances receive. But it does mean treating marijuana as a simple over-the-counter panacea for myriad physical and psychological problems is dangerous without more rigorous scientific research backing it up.

Myth 2: “Reefer Madness” Was and Remains Just a Scare Tactic

While use of the “reefer madness” was most certainly meant to dissuade people from partaking in marijuana use, there has been an overcorrection with regards to public perception of marijuana’s effect on a user’s psychological state and the substance’s potential side effects. No, chronic marijuana use does not seem to have a strong association with mortality, but it can still result in profound physical, mental, and financial harm to users and amounts to a considerable societal burden.

Frequent marijuana use (weekly or daily use) is related to increased risk of other substance abuse (Blanco, et al. 2016), poor executive function and neurocognitive deficit (Dahlgren, et al. 2016), impaired respiratory function (Gates, Jaffe and Copeland 2014; Tashkin, et al. 2002), cardiovascular disease (Hall and Degenhardt 2009; Richards, et al. 2019), and periodontal disease (Cho, Hirsch and Johnstone 2005).

Chronic users are also at risk of a condition known as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, a relatively rare syndrome involving repeated and severe episodic nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain that is relieved by exposure to hot water (Sorensen, et al. 2017).

Persistent marijuana users are at risk of downward socioeconomic mobility. Heavy users report lower incomes and achieve a lower level of education compared to non-heavy users (Gruber, et al. 2003). A longer history of marijuana dependence is associated with increased financial difficulties (e.g., loss of income, financial strain) and unemployment in early midlife. In fact, research suggests that CUD is associated with more financial difficulties than alcohol use disorder. Regular marijuana use is also associated with antisocial behavior in the workplace and lower relationship satisfaction (Cerda, et al. 2016).

More scientific research is necessary to determine the potential impact of marijuana on users’ mental health before we can confidently endorse it as an over-the-counter treatment option for people across the spectrum.

Myth 3: Marijuana Side Effects? What Side Effects?

Perhaps this is in relation to marijuana’s position vis-a-vis the other Schedule I drugs, which have very obvious side effects, but the myth that marijuana generally only has positive side effects is prevalent in the language supporting broader marijuana acceptance. However, this myth ignores much scientific evidence surrounding the potential side effects, especially those related to marijuana use amongst adolescents and human reproductive health.

Adolescents are thought to be particularly vulnerable to pathology from marijuana use, as adolescence is both a time of important brain development and when drug use frequently begins. For instance, the mean age of first-time cannabis use is 19.4 years old (Weiss, Howlett and Baler 2017; Simpson and Magid 2016). In the U.S., studies suggest cannabis use has remained stable among adolescents aged 12 to 17 over the past decade (8.2% in 2002 and 7.4% in 2014) and the prevalence of cannabis user disorder has actually decreased (Hasin 2018). However, marijuana remains the illicit drug substance most commonly abused by this age group (Simpson and Magid 2016) and there is a declining perception of the harm associated with cannabis use.

In 2015, only 32% of 12th graders perceived regular cannabis use as risky compared to 47% in 2010 and 79% in 1991. Moreover, nearly 6% of 12th graders reported daily or almost daily cannabis use (Weiss, Howlett and baler 2017). This is particularly concerning given adolescents are at increased risk of developing cannabis use disorder compared to the general population. While the lifetime risk of dependence in cannabis users has been estimated at less than one in ten, it rises to one in six in those who initiate marijuana use in adolescence (Hall and Degenhardt 2009).

The adverse psychosocial consequences of heavy cannabis use in adolescence have been well documented and are similar to the effects seen in chronic adult users. High levels of cannabis use at an early age are associated with poorer educational outcomes, lower income, greater unemployment, and lower relationship and life satisfaction (Fergusson, Boden and Horwood 2008; Brook, Lee and Finch, et al. 2013). Early and heavy cannabis use has also been associated with increased violent and criminal behavior (Ellickson and McGuigan 2000; Brook, Lee and Brown, et al. 2011) and other illicit drug use (Hall and Degenhardt 2009).

Alterations in brain structure and function may underlie some of these outcomes. Neuropsychological testing has demonstrated that long-term use of marijuana results in significant decline in executive functioning, memory, learning, and/or cognitive processing speed compared to non-users (Simpson and Magid 2016). Significant declines in intelligence quotient (IQ) have been reported in longitudinal studies of adolescents who developed marijuana dependence (Meier, et al. 2012) and in case-control studies of early-onset users compared to late-onset users (Pope Jr., et al. 2003). Of note, adult-onset heavy cannabis use was not associated with decreased IQ scores (Meier, et al. 2012).

Alterations in brain structure and function secondary to marijuana use are further supported by neuroimaging data (Jacobus and Tapert 2014). One review of neuroanatomic alterations in heavy marijuana users found that the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and the cerebellum were the most affected by regular use. Greater dose and earlier age of onset were associated with these changes. The authors noted that these areas are integral to the components of brain reward, memory, and executive-attention and may explain the deficits marijuana users show in these areas (Lorenzetti, Solowij and Yucel 2016; Stoecker, Rapp and Malters 2018). Separate research leveraging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) found that negative effects of adolescent marijuana use on hippocampal structure was maintained well into late life (Burggren, et al. 2018).

Neuronal connectivity may also be impaired in cannabis users (Houck, Bryan and Feldstein Ewing 2013). One study of adults who began to use cannabis regularly as adolescents found marked decreases in the connectivity of the fimbria of the hippocampus – a part of the brain important for memory formation (Zalesky, et al. 2012). These brain alterations may play a key role in the adverse effects experienced by adolescent heavy users.

With regards to reproductive health, marijuana use among pregnant women is following the global upward trend. The prevalence of marijuana use in pregnancy increased from 2.37% in 2002 to 3.85% in 2014. Marijuana use during pregnancy is more common among young pregnant women (7.47% in 18- to 25-year-olds compared to 2.12% in 26- to 44-year-olds). Pregnant cannabis users are more likely than non-pregnant users to report daily use (16.2% versus 12.8%) and are more likely to meet the criteria for cannabis use disorder (18.1% versus 11.4%) (Ko, et al. 2015). Women who continued to use marijuana during pregnancy often perceived no general or pregnancy-specific risk compared to nonusers and rarely received counseling regarding their marijuana use from healthcare providers (Bayrampour, et al. 2019).

Scientifically, marijuana can freely cross the placenta during pregnancy, making marijuana use during pregnancy an important issue that may affect the health of both pregnant women and their offspring. Neonates exposed to marijuana in utero are at risk of low birth weight and are more likely to need placement in the neonatal intensive care unit (Gunn, et al. 2016; Howard, et al. 2019; Mark and Terplan 2017).

In animal models, high doses of marijuana cause growth retardation and malformations in offspring (Hall and Degenhardt 2009). It is thought that marijuana exposure may impact human fetus neurodevelopment, especially executive functioning and memory, but findings have been inconsistent and more investigation is necessary (Mark and Terplan 2017; El Marroun, et al. 2018). Separately, in terms of risk to the mother, pregnant women who use marijuana were shown to have a higher risk of anemia compared to women who abstained (Gunn, et al. 2016).

Marijuana use while breastfeeding may also pose harm to newborns as cannabinoids appear in breast milk at an estimated 0.8 to 2.5% of maternal exposure. (Djulus, Moretta and Koren 2005; Metz and Stickrath 2015). It is estimated that 84% of marijuana users during pregnancy continued use during lactation (Astley and Little 19990), and one U.S. survey indicated that approximately 15% of breastfeeding mothers reported past year marijuana use (Bergeria and Heil 2015). The impact of such marijuana exposure specifically on the newborn is unknown, in part due to the substantial overlap between women who use marijuana during pregnancy and during the lactation period (Djulus, Moretta and Koren 2005; Metz and Stickrath 2015). Marijuana may also impact a woman’s ability to lactate altogether, as there is some evidence that marijuana may inhibit prolactin secretion, the key neuroendocrine mediator of lactation (Murphy, et al. 1998).

Men seeking to impregnate must also be cautious of marijuana use. Cannabis use can disrupt the signaling pathways in the male reproductive process. Both in vitro and in vivo studies suggest cannabis disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, reduces spermatogenesis, and impairs sperm function by disrupting motility, capacitation, and the acrosome reaction. These disruptions can lead to impaired reproductive potential or even infertility (du Plessis, Agarwal and Syriac 2015; Payne, et al. 2019).

Some research has even suggested that heavy paternal marijuana use can lead to behavioral changes in their offspring through epigenetic changes. In murine models, offspring of rats exposed to high levels of THC had poor attention performance and impaired stress responses (Levin, et al. 2019; Ibn Lahmar Andaloussi, Taghzouti And Abboussi 2019). Further research on the topic in human studies is necessary.

Once again, it is obvious marijuana does provide some health benefits to users, but the myriad potential side effects across a number of different health areas are being ignored. More serious scientific research is necessary to back up the claims of the medical marijuana industry in order to legitimize the substance as an appropriate course of treatment for people across a range of health issues.

Conclusion

The debate around medical marijuana and recreational marijuana is complicated. Despite that, we want to reiterate that we do not support going backward on marijuana legalization. In fact, we support it. Legalized marijuana is the future. But a reassessment of the medicinal marijuana landscape must occur and has not taken place since recreational marijuana became legal in a growing number of states.

From our perspective, there is now an overlap of philosophical, societal, and medical treatment of medicinal and recreational marijuana. This overlap creates a landscape where the potential side effects of marijuana are ignored and marijuana is cloaked in a medical legitimacy, which, as this paper shows, may not be warranted. Studies of the short- and long-term health effects of marijuana are lacking, and if marijuana is going to be recommended to more patients across the country as a treatment for various health problems, more information on its health effects is necessary.

Much of the public perception of marijuana and its effects on humans was baked into the cake long ago. But that perception of marijuana is outdated and even though it may not be as serious as other Schedule I drugs, research shows modern marijuana products are much more powerful than the marijuana previously accepted as appropriate for medicinal purposes. And when patients with serious health problems, like different forms of cancer, are seeking out medical marijuana companies, who have their own profit interests in mind, instead of licensed medical professionals, this becomes a larger public health issue.

Continuing to cloak marijuana in the legitimacy of the medical community when there is no clear evidence of its medical benefits undermines public health. This dynamic is one the United States has experienced with opiates, and it would be irresponsible to do so again with marijuana simply because of outdated perceptions of marijuana’s risks.

Citations

Astley, S. J., and R. E. Little. 1990. “Maternal marijuana use during lactation and infant development at one year.” Neurotoxicol Teratol. 167-168.

Baler, Dr. Ruben, interview by Weedless. 2021. Ruben Baler, Ph.D., on Marijuana Tolerance, Dependence, and Withdrawal (February 18).

Baron, Eric P. 2015. “Comprehensive Review of Medicinal Marijuana, Cannabinoids, and Therapeutic Implications in Medicine and Headache: What a Long Strange Trip It’s Been…” Headache. 885-916.

Bayrampour, Hamideh, Mike Zahradnik, Sarka Lisonkova, and Patti Janssen. 2019. “Women’s perspectives about cannabis use during pregnancy and the postpartum period: An integrative review.” Prev Med. 17-23.

Behrendt, S., H-U Wittchen, M. Hofler, R. Lieb, and K. Beesdo. 2009. “Transitions from first substance use to substance use disorders in adolescence: is early onset associated with a rapid escalation?” Drug Alcohol Depend. 68-78.

Bergeria, Cecilia L., and Sarah H. Heil. 2015. “Surveying Lactation Professionals Regarding Marijuana Use and Breastfeeding.” Breastfeed Med. 377-380.

Blanco, Carlos, Deborah S. Hasin, Melanie M. Wall, Ludwing Florez-Salamanca, Nicolas Hoertel, Shuai Wang, Bradley T. Kerridge, and Mark Olfson. 2016. “Cannabis Use and Risk of Psychiatric Disorders: Prospective Evidence From a US National Longitudinal Study.” JAMA Psychiatry. 388-395.

Bonnet, Udo, and Ulrich W. Preuss. 2017. “The cannabis withdrawal syndrome: current insights.” Subst Abuse Rehabil. 9-37.

Brook, Judith S., Jung Yeon Lee, Elaine N. Brown, Stephen J. Finch, and David W. Brook. 2011. “Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: Personality and social role outcomes.” Psychol Rep. 339-357.

Brook, Judith S., Jung Yeon Lee, Stephen J. Finch, Nathan Seltzer, and David W. Brook. 2013. “Adult work commitment, financial stability, and social environment as related to trajectories of marijuana use beginning in adolescence.” Subst Abus. 298-305.

Burggren, Alison C., Prabha Siddarth, Zanjbeel Mahmood, Edythe D. London, Theresa M. Harrison, David A. Merrill, Gary W. Small, and Susan Y. Brookheimer. 2018. “Subregional Hippocampal Thickness Abnormalities in Older Adults with a History of Heavy Cannabis Use.” Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 242-251.

Caputi, Theodore L. 2022. “The Use of Academic Research in Medical Cannabis Marketing: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review of Company Websites.” J Stud Alcohol Drugs 5-17.

Carliner, Hannah, Qiana L. Brown, Aaron L. Sarvet, and Deborah S. Hasin. 2017. “Cannabis use, attitudes, and legal status in the U.S.: A review.” Prev Med. 13-23.

Cerda, Magdalena, Terrie E. Moffitt, Madeline H. Meier, HonaLee Harrington, Renate Houts, Sandhya Ramrakha, Sean Hogan, Richie Poulton, and Avshalom Caspi. 2016. “Persistent cannabis dependence and alcohol dependence represent risks for midlife economic and social problems: A longitudinal cohort study.” Clin Psychol Sci. 1028-1046.

Cho, C.M., R. Hirsch, and S. Johnstone. 2005. “General and oral health implications of cannabis use.” Aust Dent J. 70-74.

Chopra, I. C., and R. N. Chopra. 1957. “The Use of the Cannabis Drugs in India.” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. January 1. Accessed February 24, 2022. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1957-01-01_1_page003.html.

Clark, Peter A., Kevin Capuzzi, and Cameron Fick. 2011. “Medical marijuana: Medical necessity versus political agenda.” Medical Science Monitor 249-261.

Clarke, Robert, and Mark Merlin. 2016. Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dahlgren, Mary Kathryn, Kelly A. Sagar, Megan T. Racine, Meredith W. Dremen, and Staci A. Gruber. 2016. “Marijuana Use Predicts Cognitive Performance on Tasks of Executive Function.” J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 298-308.

Daniller, Andrew. 2019. “Two-thirds of Americans support marijuana legalization.” Pew Research Center. November 14. Accessed January 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/14/americans-support-marijuana-legalization/.

Degenhardt, Louisa, Alize J. Ferrari, Bianca Calabria, Wayne D. Hall, Rosana E. Norman, John McGrath, Abraham D. Flaxman, et al. 2013. “The global epidemiology and contribution of cannabis use and dependence to the global burden of disease: results from the GBD 2010 study.” PLoS One.

Djulus, Josephine, Myla Moretta, and Gideon Koren. 2005. “Marijuana use and breastfeeding.” Can Fam Physician. 349-350.

du Plessis, Stefan S., Ashok Agarwal, and Arun Syriac. 2015. “Marijuana, phytocannabinoids, the endocannabinoid system, and male fertility.” J Assist Reprod Genet. 1575-1588.

El Marroun, Hanan, Qiana L. Brown, Ingunn Olea Lund, Victoria H. Coleman-Cowger, Amy M. Loree, Devika Chawla, and Yukiko Washio. 2018. “An epidemiological, developmental and clinical overview of cannabis use during pregnancy.” Prev Med. 1-5.

Ellickson, P. L., and K. A. McGuigan. 2000. “Early predictors of adolescent violence.” Am J Public Health. 566-572.

Fergusson, David M., Joseph M. Boden, and L. John Horwood. 2008. “The developmental antecedents of illicit drug use: evidence from a 25-year longitudinal study.” Drug Alcohol Depend. 165-177.

Gates, Peter, Adam Jaffe, and Jan Copeland. 2014. “Cannabis smoking and respiratory health: consideration of the literature.” Respirology. 655-662.

Green, Ted Van. 2021. “Americans overwhelmingly say marijuana should be legal for recreational or medical use.” Pew Research Center. April 16. Accessed January 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/16/americans-overwhelmingly-say-marijuana-should-be-legal-for-recreational-or-medical-use/.

Gruber, A. J., H. G. Pope, J. I. Hudson, and D. Yurgelun-Todd. 2003. “Attributes of long-term heavy cannabis users: a case-control study.” Psychol Med. 1415-1422.

Grucza, Richard A., Arpana Agrawal, Melissa J. Krauss, Patricia A. Cavazos-Rehg, and Laura J. Bierut. 2016. “Recent Trends in the Prevalence of Marijuana Use and Associated Disorders in the United States.” JAMA Psychiatry. 300-301.

Gunn, J. K.L., C. B. Rosales, K. E. Center, A. Nunez, S. J. Gibson, C. Christ, and J. E. Ehiri. 2016. “Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” BMJ Open. 6-10.

Hall, Wayne, and Louisa Degenhardt. 2009. “Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use.” The Lancet. 1383-1391.

Hasin, Deborah S. 2018. “US Epidemiology of Cannabis Use and Associated Problems.” Neuropsychopharmacology. 195-212.

Hasin, Deborah S., Tulshi D. Saha, Bradley T. Kerridge, Rise B. Goldstein, S. Patricia Chou, Haitao Zhang, Jeesun Jung, et al. 2015. “Prevalence of Marijuana Use Disorders in the United States Between 2001-2002 and 2012-2013.” JAMA Psychiatry. 1235-1242.

Hedden, Sarra L., Joel Kennet, Rachel Lipari, Grace Medley, Peter Tice, Elizabeth A.P. Copello, and Larry A. Kroutil. 2015. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality.

Hines, Lindsey A., Katherine I. Morley, John Strang, Arpana Agrawal, Elliot C. Nelson, Dixie Statham, Nicholas G. Martin, and Michael T. Lynskey. 2015. “The association between speed of transition from initiation to subsequent use of cannabis and later problematic cannabis use, abuse and dependence.” Addiction. 1311-1320.

Houck, Jon M., Angela D. Bryan, and Sarah W. Feldstein Ewing. 2013. “Functional connectivity and cannabis use in high-risk adolescents.” Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 414-423.

Howard, D. Scott, David N. Dhanraj, C. Ganga Devaiah, and Donna S. Lambers. 2019. “Cannabis Use Based on Urine Drug Screens in Pregnancy and Its Association With Infant Birth Weight.” J Addict Med. 436-441.

Hughes, John R., Shelly Naud, Alan J. Budney, James R. Fingar, and Peter W. Callas. 2016. “Attempts to stop or reduce daily cannabis use: An intensive natural history study.” Psychol Addict Behav. 389-397.

Ibn Lahmar Andaloussi, Zineb, Khalid Taghzouti, and Oualid Abboussi. 2019. “Behavioural and epigenetic effects of paternal exposure to cannabinoids during adolescence on offspring vulnerability to stress.” Int J Dev Neruosci. 48-54.

Jacobus, Joanna, and Susan F. Tapert. 2014. “Effects of cannabis on the adolescent brain.” Curr Pharm Des. 2168-2193.

Kennedy, Brian, Alec Tyson, and Cary Funk. 2022. “Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Decline.” Pew Research Center. February 15. Accessed February 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2022/02/15/americans-trust-in-scientists-other-groups-declines/.

Ko, Jean Y., Sherry L. Farrr, Van T. Tong, Andreea A. Creanga, and William M. Callaghan. 2015. “Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age.” Am J Obstet Gynecol. 201.

Lee, Dayong, Jennifer R. Schroeder, Erin L. Karschner, Robert S. Goodwin, Jussi Hirvonen, David A. Gorelick, and Marilyn A. Huestis. 2014. “Cannabis Withdrawal in Chronic, Frequent Cannabis Smokers during Sustained Abstinence within a Closed Residential Environment.” Am J Addict. 234-242.

Levin, Edward D., Andrew B. Hawkey, Brandon J. Hall, Marty Cauley, Susan Slade, Elisa Yazdani, Bruny Kenou, et al. 2019. “Paternal THC exposure in rats causes long-lasting neurobehavioral effects in the offspring.” Neurotoxicol Teratol. 74.

Levy, Natalie S., Pia M. Mauro, Christine M. Mauro, Luis E. Segura, and Silvia S. Martins. 2021. “Joint perceptions of the risk and availability of Cannabis in the United States, 2002-2018.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

Li, H. L. 1974. “An archaeological and historical account of cannabis in China.” Economic Botany. 437-448.

Liu, W. M., and Thomas B. Powles. 2006. “Cannabinoids: Do they have a Role in Cancer Therapy?” Letters in Drug Design & Discovery. 76-82.

Livne, Ofir, Dvora Shmulewitz, Shaul Lev-Ran, and Deborah S. Hasin. 2019. “DSM-5 cannabis withdrawal syndrome: Demographic and clinical correlates in U.S. adults.” Drug Alcohol Depend. 170-177.

Lopez-Quintero, Catalina, Jose Pérez de los Cobos, Deborah S. Hasin, Mayumi Okuda, Shuai Wang, Bridget F. Grant, and Carlos Blanco. 2011. “Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC).” Drug Alcohol Depend. 120-130.

Lorenzetti, Valentina, Nadia Solowij, and Murat Yucel. 2016. “The Role of Cannabinoids in Neuroanatomic Alterations in Cannabis Users.” Biol Psychiatry. 17-31.

Mark, Katrina, and Mishka Terplan. 2017. “Cannabis and pregnancy: Maternal child health implications during a period of drug policy liberalization.” Prev Med. 46-49.

Meier, Madeline H., Avshalom Caspi, Antony Ambler, HonaLee Harrington, Renate Houts, Richard S.E. Keefe, Kay McDonald, Aimee Ward, Richie Poulton, and Terrie E. Moffitt. 2012. “Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2657-2664.

Metz, Torri D., and Elaine H. Stickrath. 2015. “Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence.” Am J Obstet Gynecol. 761-778.

Murphy, L. L., R. M. Munoz, B. A. Adrian, and M. A. Villanua. 1998. “Function of cannabinoid receptors in the neuroendocrine regulation of hormone secretion.” Neurobiol Dis. 432-446.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. 2020. “Marijuana Research Report.” National Institute on Drug Abuse. July. Accessed January 2022. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana/marijuana-safe-effective-medicine.

O’Shaughnessy, W. B. 1843. “ON the Preparations of the Indian Hemp, or Gunjah: Cannabis Indica Their Effects on the Animal System in Health, and their Utility in the Treatment of Tetanus and other Convulsive Diseases.” Provincial Medical Journal and Retrospect of the Medical Sciences. 363-369.

Pain, Stephanie. 2015. “A potted history.” Nature. 10-11.

Patel, Jason, and Raman Marwaha. 2022. Cannabis Use Disorder. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing.

Payne, Kelly S., Daniel J. Mazur, James M. Hotaling, and Alexander W. Pastuszak. 2019. “Cannabis and Male Fertility: A Systematic Review.” J Urol. 674-681.

Pisanti, Simona, and Maurizio Bifulco. 2017. “Modern History of Medical Cannabis: From Widespread Use to Prohibitionism and Back.” Trends Pharmacol Science. 195-198.

Pope Jr., Harrison G., Amanda J. Gruber, James I. Hudson, Geoffrey Cohane, Marilyn A. Huestis, and Deborah Yurgelun-Todd. 2003. “Early-onset cannabis use and cognitive deficits: what is the nature of the association?” Drug Alcohol Depend. 303-310.

Pulay, Attila J, Deborah A. Dawson, Deborah S. Hasin, Rise B. Goldstein, W. June Ruan, Roger P. Pickering, Boji Huant, S. Patricia Chou, and Bridget F. Grant. 2008. “Violent behavior and DSM-IV psychiatric disorders: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions.” J Clin Psychiatry. 12-22.

Richards, John R., Gagan D. Singh, Aman K. Parikh, and Sandhya Venugopal. 2019. “Acute coronary syndrome after cannabis use: Correlation with quantitative toxicology testing.” Am J Emerg Med. 1007.

Russo, Ethan B. 2007. “History of cannabis and its preparations in saga, science, and sobriquet.” Chemistry & Biodiversity. 1614-1648.

Russo, Ethan B. 2017. “History of Cannabis as Medicine: Nineteenth Century Irish Physicians and Correlations of Their Observations to Modern Research.” In Cannabis sativa L. – Botany and Biotechnology, Ed.: Suman Chandra, Hemant Lata and Mahmoud A. ElSohly, 63-78. New York: Springer.

Schlienz, Nicolas J., Alan J. Budney, Dustin C. Lee, and Ryan Vandrey. 2017. “Cannabis Withdrawal: A Review of Neurobiological Mechanisms and Sex Differences.” Curr Addict Rep. 75-81.

Sexton, Michelle, Carrie Cuttler, and Laurie K. Mischley. 2019. “A Survey of Cannabis Acue Effects and Withdrawal Symptoms: Differential Responses Across User Types and Age.” J Altern Complement Med. 326-335.

Simpson, Annabelle K., and Viktoriya Magid. 2016. “Cannabis Use Disorder in Adolescence.” Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 431-443.

Sorensen, Cecilia J., Kristen DeSanto, Laura Borgelt, Kristina T. Phillips, and Andrew A. Monte. 2017. “Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment – a Systematic Review.” J Med Toxicol. 71-87.

Stoecker, William V., Emily E. Rapp, and Joseph M. Malters. 2018. “Marijuana Use in the Era of Changing Cannabis Laws: What Are the Risks? Who is Most at Risk?” Mo Med. 398-404.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2017. Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2016. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2004-2014. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Tashkin, Donald P., Gayle C. Galdwin, Theodore Sarafian, Steven Dubinett, and Michael D. Roth. 2002. “Respiratory and immunologic consequences of marijuana smoking.” J Clin Pharmacol. 71-81.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2020. “FDA and Cannabis: Research and Drug Approval Process.” U.S. Food & Drug Administration. October 1. Accessed January 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-cannabis-research-and-drug-approval-process.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2018. “FDA: What We Do.” U.S. Food & Drug Administration. March 28. Accessed January 2022. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/what-we-do.

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. 2015. “FDA’s Drug Review Process: Continued.” U.S. Food & Drug Administration. August 24. Accessed January 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/information-consumers-and-patients-drugs/fdas-drug-review-process-continued.

van der Pol, Peggy, Nienke Liebregts, Ron de Graaf, Dirk J. Korf, Wim van den Brink, and Margriet van Laar. 2013. “Predicting the transition from frequent cannabis use to cannabis dependence: a three-year prospective study.” Drug Alcohol Depend. 352-359.

Weiss, Susan R.B., Katia D. Howlett, and Ruben D. Baler. 2017. “Building smart cannabis policy from the science up.” International Journal of Drug Policy. 39-49.

Wittchen, Hans-Ulrich, Christine Froglich, Silke Behrendt, Agnes Gunther, Jurgen Rehm, Petra Zimmermann, Roselind Lieb, and Axel Perkonigg. 2007. “Cannabis use and cannabis use disorders and their relationship to mental disorders: a 10-year prospective-longitudinal community study in adolescents.” Drug Alcohol Depend. 60-70.

Zalesky, Andrew, Nadia Solowij, Murat Yucel, Dan I. Lubman, Michael Takagi, Ian H. Harding, Valentina Lorenzetti, et al. 2012. “Effect of long-term cannabis use on axonal fibre connectivity.” Brain. 2245-2255.

Zvolensky, Michael J., Daniel J. Paulus, Lorra Garey, Kara Manning, Julianna B.D. Hogan, Julia D. Buckner, Andrew H. Rogers, and R. Kathryn McHugh. 2018. “Perceived barriers for cannabis cessation; Relations to cannabis use problems, withdrawal symptoms, and self-efficacy for quitting.” Addict Behav. 45-51.